Hemifacial spasm is a movement disorder of the facial muscles. It manifests itself in involuntary, repetitive, unilateral contractions of the facial muscles, which are often disfiguring and painful and cause a high degree of suffering in those affected. Not infrequently, social isolation and depression are the result. If left untreated, the symptoms of hemispasm facialis remain lifelong, because the cause of the spasms is usually a constriction of the facial nerve by a blood vessel. Only surgical relief of the compressed facial nerve resolves the cause and thus the distressing symptoms.

The unknown disease

In a recent study, it was found that patients often suffer from the symptoms for more than 8 years before they learn about the possibilities of surgery. The Department of Neurosurgery at Inselspital has therefore launched a campaign to increase awareness of this condition. Permanent improvement or cure are usually only possible through microsurgical operation *.

How common is hemifacial spasm?

About 10 out of 100,000 people suffer from hemifacial spasm. For Switzerland, that is about 800 sufferers. The typical age of onset is between the 45th and 65th year of life, whereby women are more frequently affected than men (in a ratio of 2:1) and left-sided hemifacial spasm is more frequent than right-sided hemifacial spasm (also in a ratio of 2:1). Bilateral hemifacial spasm is very rare.

What causes hemifacial spasm?

The trigger is usually a blood vessel (artery or vein) that exerts pressure on the facial nerve. The most sensitive site of the facial nerve is at the transition zone from central myelin to peripheral myelin, immediately at the exit of the facial nerve from the brainstem. This so-called root entry zone is 3–5 mm long. Now, when a cerebral artery makes direct contact with this sensitive zone, the sustained pulsation of the artery can cause irritation to the facial nerve.

Cerebral arteries run in loops through the subarachnoid space in everyone and show lengthening or widening with age. Therefore, new contact formation is possible throughout life. In addition, tumors, multiple sclerosis or brainstem infarcts can also be the cause of spontaneous excitation formation.

What are the symptoms of hemifacial spasm?

Typical symptoms of hemifacial spasm are:

- involuntary, painful spasms of the facial muscles (starting from one eye, they spread to the rest of the face upper remain limited to the upper or lower half of the face)

- only one side of the face is affected by spasms

- multiple spasms in one minute

- spasms even during sleep

- possible increased lacrimation

- possible disturbance of bilateral vision

- increased symptoms due to mental tension and stress

- after long duration of the disease also paralysis of the facial muscles

Although the listed complaints are very typical for a hemispasmus facialis, other causes, such as a dystonia, a facial tic or other types of spasms must be excluded.

How is hemifacial spasm diagnosed?

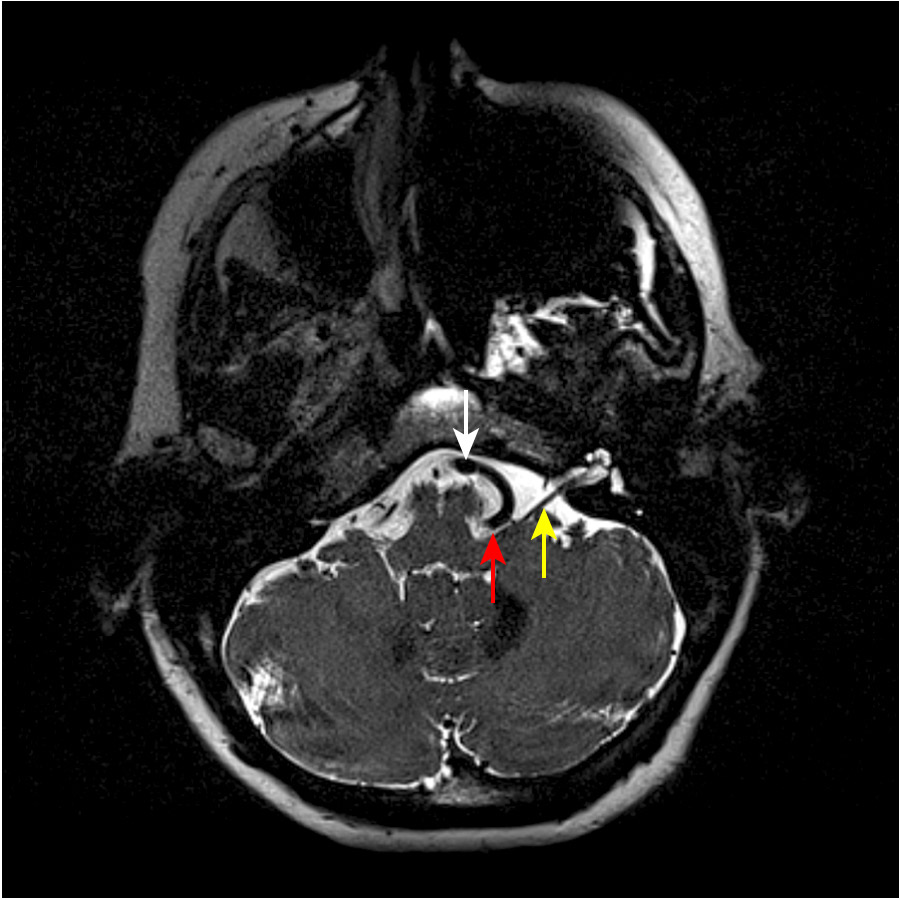

In our opinion, evidence of contact between the blood vessel (artery or vein) and the brainstem or facial nerve is absolutely essential. This is done with the help of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

However, this is not always easy because the facial nerve is still close to the brain stem in the initial segment. The nerve cannot be clearly distinguished from the brain stem in the MRI image. Axial, very thinly layered special CISS sequences are always necessary for successful imaging. There are typically loops of the anterior inferior cerebellar artery (AICA) or the posterior inferior cerebellar artery (PICA) that touch the facial nerve or the brainstem directly below the nerve.

MRI is also used to rule out other possible causes of the spasms.

What are the treatment options?

If hemifacial spasm is left untreated, there is very rarely improvement in symptoms. Depending on the severity of symptoms and degree of impairment, hemifacial spasm can be treated symptomatically or causally.

Drug therapy

At the start of treatment, carbamazepine, clonazepam, baclofen or gabapentin are used to combat the symptoms. The success rate is usually low or the improvement is not long-lasting. These medications are therefore only suitable for the treatment of very mild forms *. Fatigue and tiredness are possible side-effects of the medication.

Injection of botulinum toxin

Injection of botulinum toxin into the facial muscles initially alleviates the symptoms in 90% of cases. In 10–20% of cases, however, temporary side-effects such as seeing double, drooping eyelids (ptosis) or facial paralysis can occur. The duration of action of the injection is 3–4 months. The botulinum toxin injection can be repeated, but it loses its effectiveness over time. This therapy does not lead to a cure, but must be continued indefinitely.

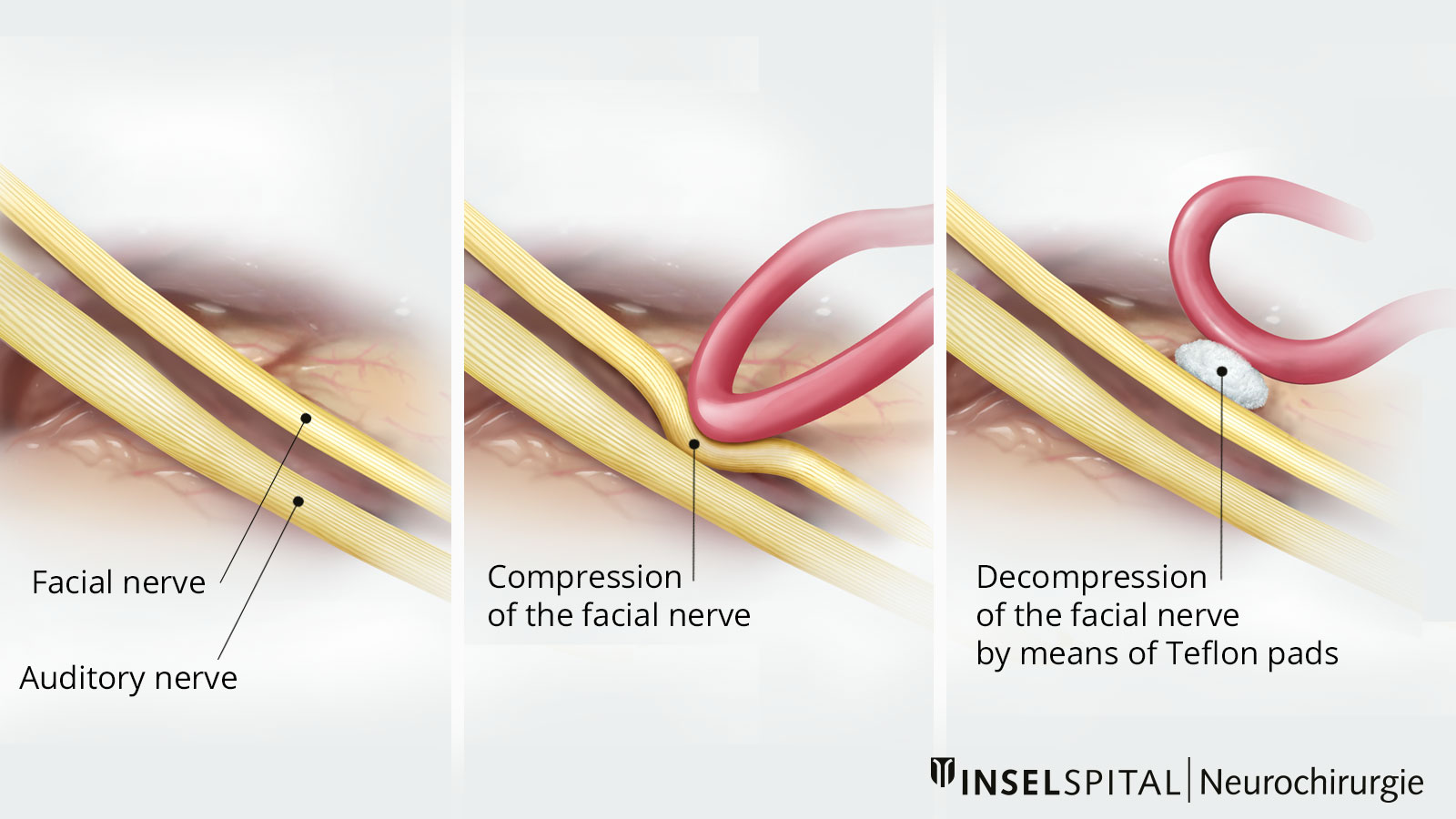

Surgery: the treatment with a 90% chance of cure

An operation is currently the only option that results in a long-term improvement or cure. The surgical technique used is similar to microvascular decompression which is used for treating trigeminal neuralgia. In principle, the pulsating artery (occasionally also the vein) is detached from the facial nerve under high microscopic magnification and slightly displaced so that it is no longer in contact with the nerve. A Teflon strip is then inserted between the artery and the nerve to prevent the blood vessel from slipping back and irritating the nerve again.

It is particularly important that the operation is carried out under the highest safety standards using special monitoring techniques. The nerve conduction and excitability of the facial nerve are monitored. The moment the surgeon moves the vascular loop that is causing the problem away from the nerve, the so-called "lateral spread", that is, the overexcitability of the facial nerve, disappears. With the help of these techniques, the surgical preparation and displacement of the vascular loop can be precisely guided and the result of the surgery can be predicted.

Success of the operation

The success rate is high. Improvement usually occurs one to two days after the operation, but sometimes only after some days or weeks following the procedure.

Six months after the operation, 80–90% of the patients are symptom-free or show a reduction in spasms of more than 90%.

Just 5–10% of the patients experience only a partial improvement, and in 5–10% of patients the operation does not improve the symptoms significantly.

Furthermore, 10% of the patients with initially good surgical results may experience a relapse, i.e. a recurrence of the symptoms.

In a metastudy covering 22 studies and data from a total of 5 685 patients, 91.1% of all patients were considered cured after a median observation period of almost 3 years. Recurrences occurred in only 2.4% of patients who underwent primary successful surgery *, *. If no success occurs initially, it should be evaluated whether a repeat operation is possible, since recurrence of the neurovascular conflict may occur due to displacement of the artery.

Complication rate of the operation

The complication rate is 3% for hearing loss on the operated side, 2% for dizziness, and less than 0.5% for a life-threatening complication such as postoperative hemorrhage or stroke.

In 3–5% of cases, there is delayed paralysis of the facial muscles (facialis palsy), which occurs about 1-2 weeks after surgery and completely resolves in almost all cases. A persistent facialis paresis was described in the mentioned metastudy in only 0.9% of all cases *.

-

Rosenstengel C, Matthes M, Baldauf J, Fleck S, Schroeder H. Hemifacial Spasm. Deutsches Aerzteblatt Online. 2012;.

-

Nilsen B, Le K, Dietrichs E. Prevalence of hemifacial spasm in Oslo, Norway. Neurology. 2004;63(8):1532-1533.

-

Raabe A, Jaiimsin A, Seifert V, Beck J. Use of a strip-clip technique to maintain transposition of a vertebral artery in microvascular decompression surgery. Acta Neurochirurgica. 2011;153(12):2393-2395.

-

Miller L, Miller V. Safety and effectiveness of microvascular decompression for treatment of hemifacial spasm: a systematic review. British Journal of Neurosurgery. 2011;26(4):438-444.