Vestibular schwannoma is a benign tumor of the vestibular and auditory nerves. Treatment of vestibular schwannoma depends on the size, growth rate of the tumor, unilateral or bilateral occurrence, presence of hearing impairment, and age of the patient. If treatment is necessary, microsurgical removal can be performed.

The former name "acoustic neuroma" is outdated, as it is not entirely anatomically correct. The correct term is vestibular schwannoma.

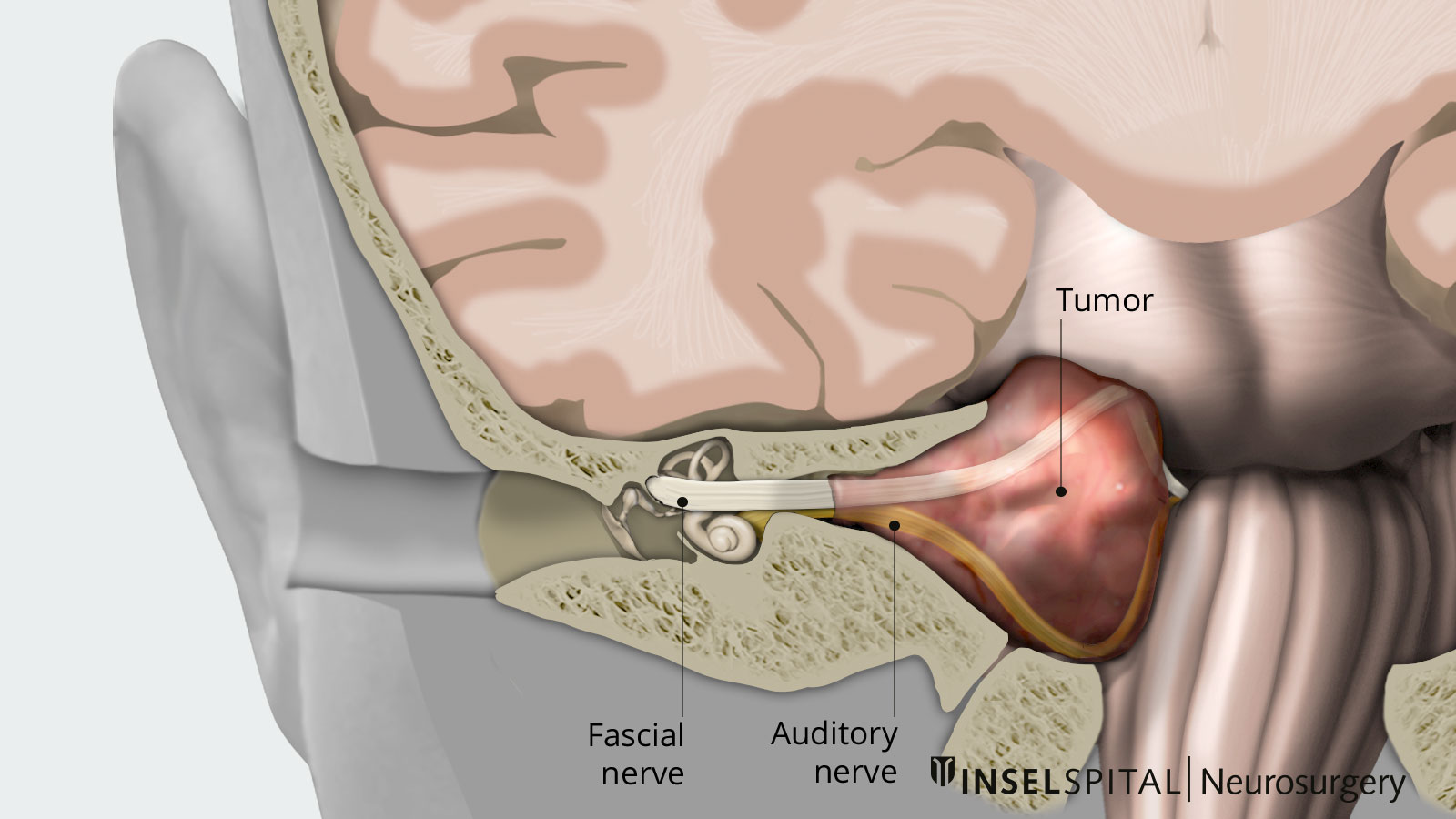

Vestibular schwannomas arise from Schwann cells of the vestibular nerve, which together with the cochlear nerve forms the VIIIth cranial nerve, the vestibulocochlear nerve. It is the auditory and vestibular nerve and runs from the inner ear through the internal auditory canal and the cerebellopontine angle into the brainstem. Schwann cells are connective tissue cells that form the myelin layer of cranial nerves. Vestibular schwannomas develop when there is a sporadic or genetic loss of a tumor suppressor gene on chromosome 22.

In most cases, the tumor occurs unilaterally. The exception is the genetic disease neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2), which can lead to bilateral vestibular schwannomas in combination with other benign tumors of the central nervous system.

How common are vestibular schwannomas?

Statistically, 1–1.5 people per 100,000 develop a vestibular schwannoma each year. Most cases occur after the age of 30, and 95% of them are unilateral tumors. According to the current state of knowledge, there are no known risk factors that lead to the development of vestibular schwannoma, except for the hereditary form (NF2).

What symptoms do vestibular schwannomas cause?

The three most common symptoms of vestibular schwannoma are *:

- slow hearing loss (98%)

- tinnitus (70%)

- dizziness (70%)

Most often, the patient first notices a one-sided, slow decline in hearing. This typically becomes noticeable when a patient can no longer make phone calls well in one ear. However, hearing loss often goes unnoticed for quite a while because it occurs gradually and over a long period of time. It is caused by compression of the immediately adjacent cochlear nerve, also known as the acustic or auditory nerve.

Other symptoms depend on the size of the tumor. In larger vestibular schwannomas, compression of the adjacent cranial nerves, especially the facial nerve (facial muscle nerve) and the trigeminal nerve (facial sensory nerve) may occur. As a result, hemiplegia of the facial muscles or sensory disturbances of the face may occur.

If the tumor continues to grow, compression of the brain stem may also occur, which manifests itself in gait or coordination disorders.

A possible complication may also be cerebrospinal fluid circulation impairment (CSF circulation disorder). In this situation, a vestibular schwannoma can become life-threatening.

Small vestibular schwannomas may be asymptomatic and are not infrequently discovered as an incidental finding when MRI of the skull is performed.

How are vestibular schwannomas diagnosed?

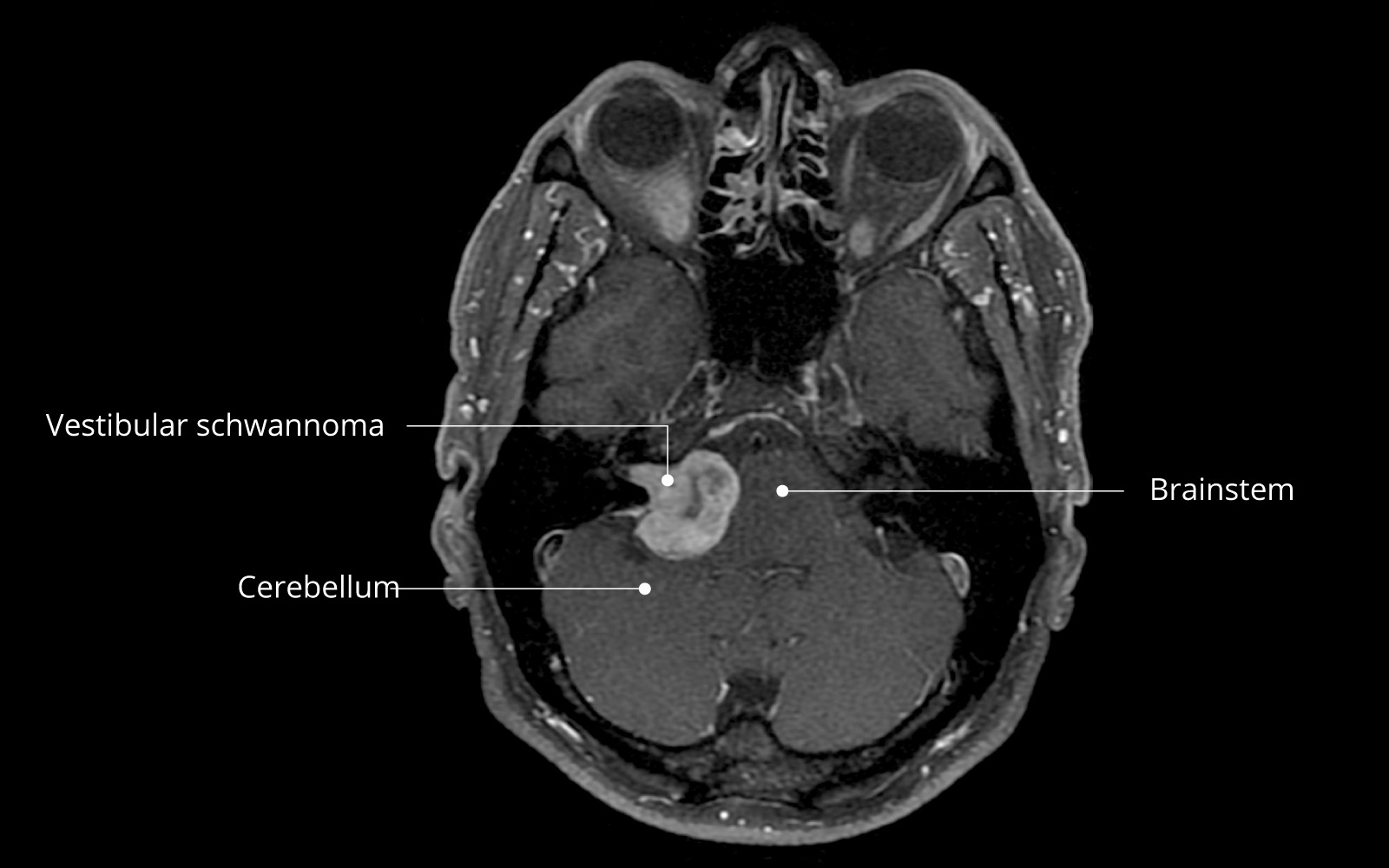

Tumors of the cerebellopontine angle are best imaged on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Vestibular schwannomas are tumors that take up contrast well and show up homogeneously or also cystic in the MRI image. For small and medium-sized tumors, a unique MRI sequence, the CISS sequence, can be performed to determine the anatomic relationship of the tumor to the adjacent cranial nerves.

In addition, pure tone audiometry is performed as a standard procedure when a tumor is diagnosed in the cerebellopontine angle. In this procedure, subjective hearing for tones is measured to determine the extent of hearing loss. This measurement can also be used for follow-up in addition to MR imaging in patients treated conservatively.

Differential diagnoses

There are also diseases with a similar symptomatology as vestibular schwannoma, which must be diagnostically distinguished from it. These include meningioma of the cerebellopontine angle. Other very rare differential diagnoses of tumors of the cerebellopontine angle are schwannomas of other cranial nerves, metastases, lymphomas or inflammatory diseases such as sarcoidosis.

How are vestibular schwannomas classified?

In order to more easily decide on a suitable therapy and, of course, to better assess the risk of postoperative loss of cranial nerve function in the auditory and vestibular nerve (vestibulocochlear nerve or CN VIII) or the facial nerve (CN VII), vestibular schwannomas are classified on imaging according to size and compressive character. One of the most commonly used gradings is the KOOS classification *.

KOOS grading scale

| KOOS grade | Description | Tumor size |

|---|---|---|

| I | Small intracanalicular tumor located only in the internal auditory canal (meatus acusticus internus). | < 10 mm |

| II | Mainly intracanalicular tumor with protrusion into the cerebellopontine angle but without contact with the brainstem. | < 20 mm |

| III | Tumor localized mainly in the cerebellopontine angle with contact to the brainstem but without compression. | < 30 mm |

| IV | Large tumor with compression of the brainstem and surrounding cranial nerves. | > 30 mm |

How are vestibular schwannomas treated?

Treatment is based primarily on the size of the tumor, its growth behavior, and the patient's symptoms. An optimal, individualized treatment recommendation for each patient is made at Inselspital by the interdisciplinary Tumor Board. Each patient's case is discussed by specialists from neurosurgery, radiation oncology, otolaryngology, oncology, and neuroradiology.

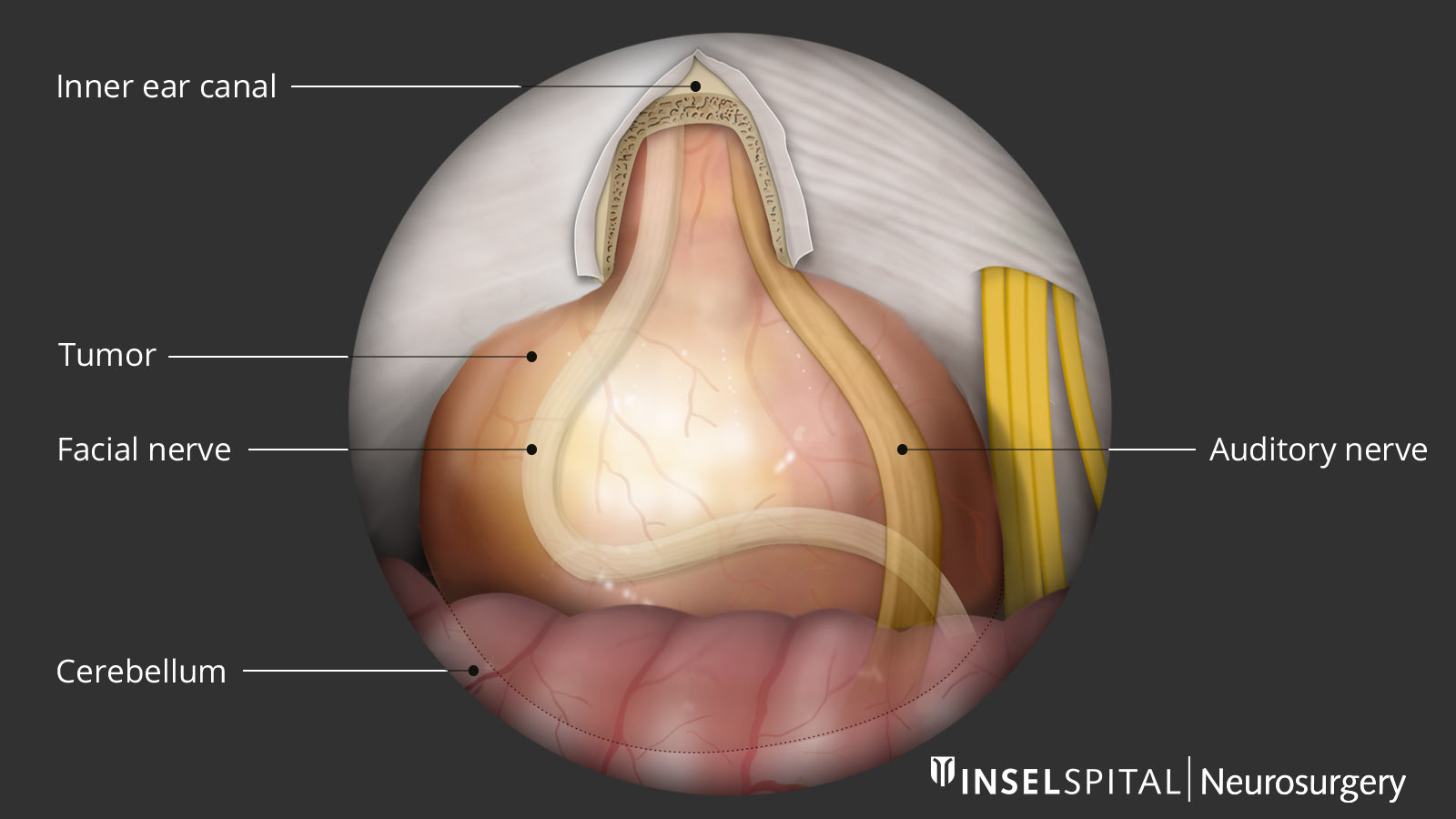

According to the modern concept, preserving the facial nerve function has priority over complete tumor resection. Even in the best hands, the rate for severe facial paralysis in complete removal of large tumors is more than 20%, according to the results in the international literature. Therefore, surgery is supported by special intraoperative neuromonitoring and is usually already planned as subtotal surgery. Also in case of incomplete facial paresis, the possible functional and cosmetic deficits weigh much more heavily than the slow, often absent growth of a small residual tumor.

Treatment alternatives are radiosurgery or, in rare cases, chemotherapy. A wait-and-see approach with regular follow-up is also common.

Recommendations depending on tumor grading

KOOS I

In KOOS-I tumors, a wait-and-see approach is possible. Tumor growth is monitored with regular MRIs and hearing tests. This is especially recommended for bilateral vestibular schwannomas with intact hearing in patients with neurofibromatosis type 2. If there is relevant tumor growth or hearing deterioration, either microsurgical treatment or radiosurgical irradiation can be considered.

KOOS II

For KOOS-II tumors, a wait-and-see approach is also possible in some instances, especially in elderly patients or patients with various diseases. However, the chances of hearing preserving surgery are much better in the early stages and should therefore be discussed. Treatment options are either microsurgical tumor removal or radiosurgical irradiation.

KOOS III und IV

In the case of a KOOS III or IV tumor, immediate treatment is indicated. In this case, microsurgical tumor removal is usually preferable to radiosurgery in order to reduce the compressive effect on the surrounding tissue.

Microsurgery

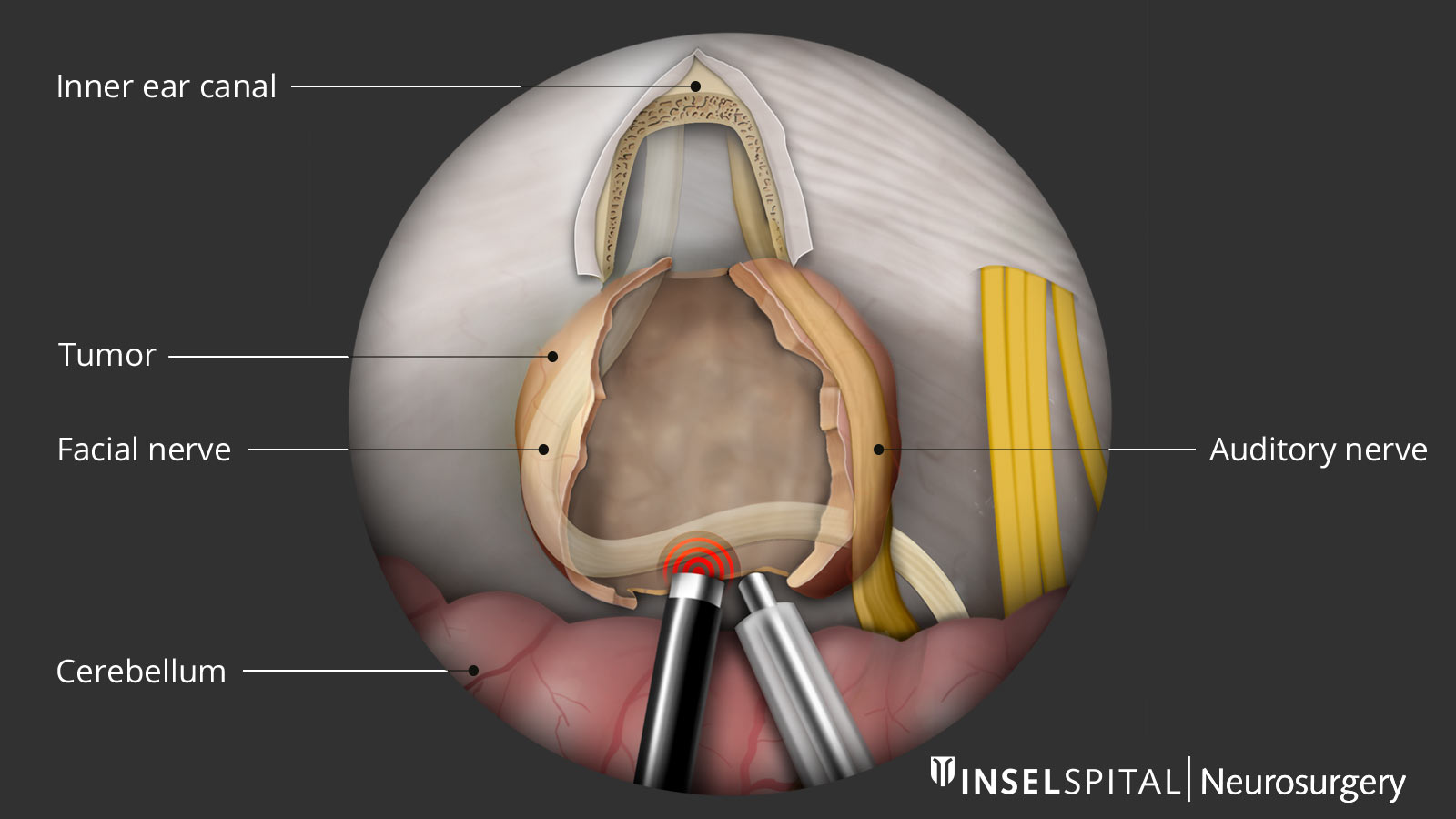

Neurosurgical resection of vestibular schwannoma is usually performed through a skin incision behind the ear, the retrosigmoid approach. Surgery is performed with a surgical microscope under high magnification. The risk of postoperative hearing loss depends mainly on the tumor size and pre-existing hearing loss.

Intraoperative neuromonitoring

To reduce the risk of cranial nerve injury during surgery, special neurophysiological monitoring is performed as standard at Inselspital. This involves monitoring auditory function, the facial nerve, the swallowing nerve, and other cranial nerves, and the motor pathway and sensitive fibers during surgery. Using the technique of transcranial stimulation of the facial nerve and the continuous "radar" function of the surgical instrument developed by us, the surgeon can locate the facial nerve through the depth of the tumor before it is visible.

In some patients, a small tumor remnant must be left to preserve the auditory or facial nerve functions. This tumor remnant can be followed up later with radiosurgery if necessary. Balance disorders are prevalent after surgery but are usually temporary. Other complications are rare.

Alternatively, it is possible to remove the tumor through a translabyrinthine approach. In this operation, the specialists of otorhinolaryngology perform the access, and the neurosurgeon then operates through the inner ear. The disadvantage of this technique is an almost 100% risk of postoperative hearing loss, so this option can be performed only in patients with pre-existing complete hearing loss.

Radiosurgery

Radiosurgery is a highly focused and high-dose single radiation treatment representing a treatment alternative to open surgery for small, well-defined tumors. At Inselspital, the latest generation of technology is used for this purpose: a computer-controlled robotic arm – the Cyberknife – administers the high dose of radiation with razor-sharp precision.

Combination of microsurgery and radiosurgery

In some instances, it makes sense to use microsurgery and radiosurgery in combination. This is the case, for example, if a relevant tumor remnant is still present after microsurgery or if a tumor that has already been operated on has grown again.

New treatment options

Particularly in patients with bilateral vestibular schwannomas, low-dose drug therapy with Avastin® (bevacizumab) may be attempted to halt tumor growth and preserve hearing function for as long as possible *.

Why you should seek treatment at Inselspital

To prevent cranial nerve deficits during surgery, in particular paralysis of the facial nerve or damage to the acustic nerve, intraoperative neurophysiological monitoring is performed as standard at Inselspital. This unique method of continuous monitoring of the facial nerve was developed and scientifically published at the Department of Neurosurgery at Inselspital. This monitoring allows precise tumor removal while sparing the facial nerve and offers our patients the highest possible safety *.

-

Greenberg MS. Handbook of Neurosurgery. Thieme; 2016:1664.

-

Koos W, Day J, Matula C, Levy D. Neurotopographic considerations in the microsurgical treatment of small acoustic neurinomas. Journal of Neurosurgery. 1998;88(3):506-512.

-

Van Gompel J, Agazzi S, Carlson M, Adewumi D, Hadjipanayis C, Uhm J et al. Congress of Neurological Surgeons Systematic Review and Evidence-Based Guidelines on Emerging Therapies for the Treatment of Patients With Vestibular Schwannomas. Neurosurgery. 2017;82(2):E52-E54.

-

Seidel K, Biner M, Zubak I, Rychen J, Beck J, Raabe A. Continuous dynamic mapping to avoid accidental injury of the facial nerve during surgery for large vestibular schwannomas. Neurosurgical Review. 2018;43(1):241-248.