The majority of spinal tumors are metastases from tumors outside the spine. Up to 10% of cancer patients develop spinal metastases in the course of their disease. The most common primary tumors are breast, prostate and bronchial carcinomas. Symptoms of vertebral metastases are often pain in the spine, possibly radiating to the arms, thorax or legs. Due to the limited space in the spine, metastases can lead to rapidly progressive neurological deficits and even paraplegia as they grow.

How frequent are vertebral metastases?

Due to the ever-improving prognosis of cancer patients, metastases to the spine are being diagnosed with increasing frequency. They now occur in 10% of all carcinoma patients. Men are affected slightly more than women. The diagnosis is most often made in middle-aged patients (40–65 years). In childhood, metastases are very rare. Here, intramedullary tumors are more common. These are usually tumors that are intrinsic to the brain.

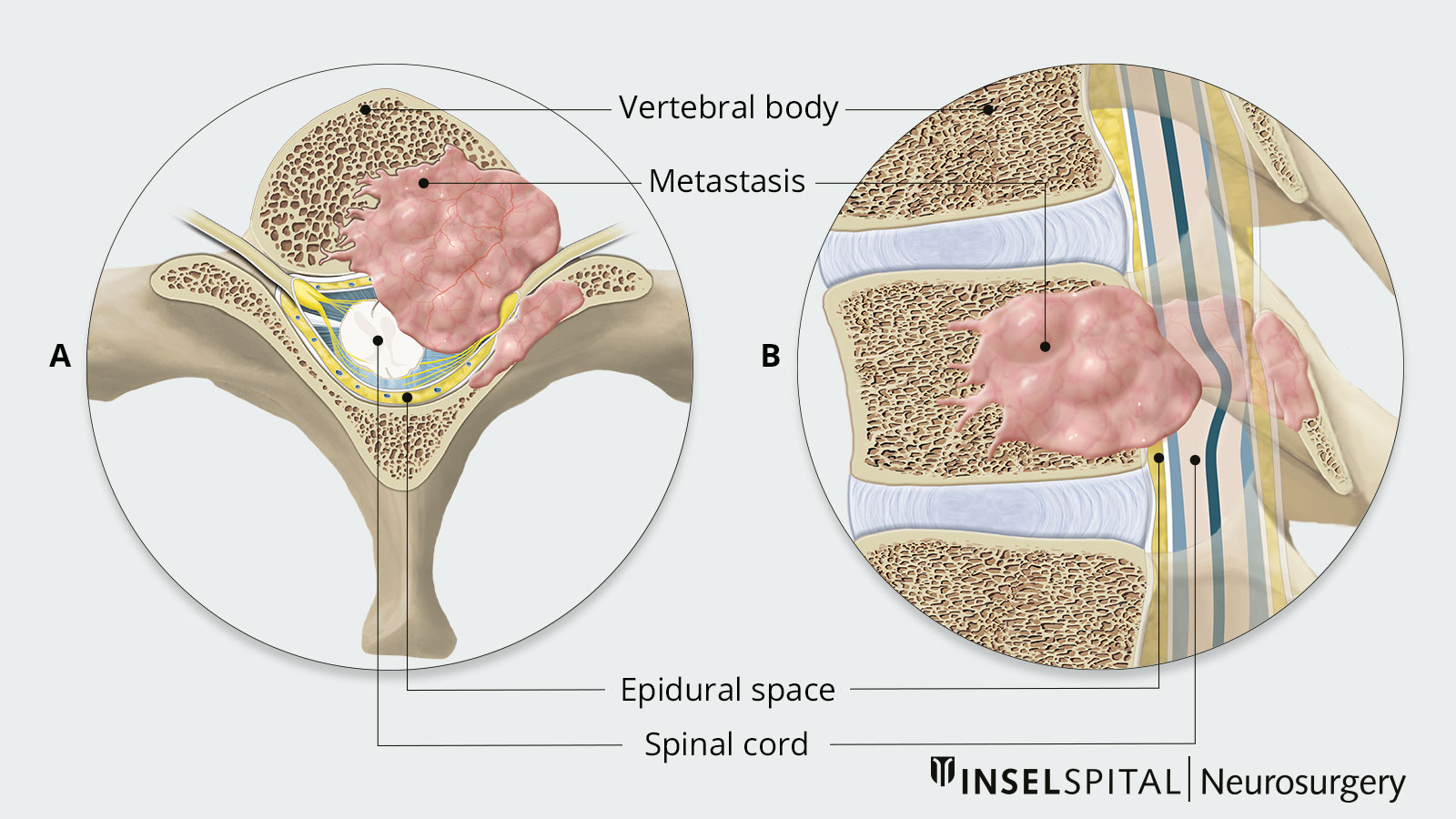

After the liver and lungs, bone is the third most common site of metastasis, with 2/3 of these bone metastases affecting the spine *. Metastasis to the spine usually occurs via the bloodstream. There, the vertebral bodies are usually affected first. However, as the metastases grow from transpedicular to epidural, the spinal cord is increasingly affected. A manifestation primarily lateral or dorsal to the spinal cord occurs much less frequently. The vast majority of spinal metastases do not grow into the dura, so that intradural spread occurs in only 2–4% of cases and intramedullary spread in only 1–2% of cases *.

In principle, any type of malignant tumor disease can lead to metastases in the spine. However, lung, breast, gastrointestinal, prostate, renal cell carcinomas, or lymphomas frequently occur in about 80% of patients *.

Metastases in the spine can also lead to the initial diagnosis of carcinoma (in 5–10% of all cases). Proportionally to the length of the cervical, thoracic and lumbar segments, the thoracic spine (thoracic spine) is most frequently affected (mostly BWK 4-BWK 7) with 50–60% of cases. It should be noted that the majority of prostate cancer metastases occur in the lumbar spine (lumbar spine). In more than half of the patients with vertebral metastases, several spine levels are affected, and in 10–38% of the patients, metastasis to different, non-adjacent segments occurs.

How are vertebral metastases classified?

Spinal tumors can be divided into three groups according to their location:

- Extradural tumors form the majority (55%) and grow in the epidural space or in the vertebral body area (e.g. metastases)

- Intradural extramedullary tumors form the second largest group (40%) with origin in the area of leptomeninges or nerve roots (e.g. meningeomas, neurinomas)

- Intradural intramedullary tumors are much rarer and grow within the spinal cord (e.g. ependymomas, gliomas)

What are the symptoms of vertebral metastases?

Spinal metastases can cause symptoms when they pressure nerve roots and the myelon, a nerve cord in the spinal canal that contains important motor and sensory nerve pathways. Generally, spinal metastases have a relatively long latency. On average, 2 months elapse between the onset of the first symptoms and diagnosis. At the beginning, patients usually complain of persistent, therapy-resistant pain without an identifiable cause, which occurs predominantly at night. This is by far the most common symptom, accounting for 95%.

A distinction is made between the

- local pain which usually occurs in the affected spinal segment and increases when lying down (especially at night)

- radicular pain radiating from the affected nerve root to the area supplied by the nerve, e.g., girdling in the chest, arms, or legs. This pain has a sharp, electrifying character.

Motor and autonomic functional limitations are the second most common symptoms, affecting 85% of patients with vertebral metastases. This reduces strength in the legs and/or arms, which can extend to complete paralysis. 76% of patients already suffer from motor weakness at the time of diagnosis. 15% are even affected by paraplegia. Of these, only less than 5% will be able to walk again after therapy.

In addition, there are often autonomic disorders such as bladder emptying disorders, rectal dysfunction, and impotence. These symptoms are clear indications of a pronounced compression of the spinal cord. This also includes sensory disturbances, which can manifest in paresthesia and numbness (anesthesia, hypesthesia, or paresthesia). In this context, especially when manifesting in the cervical or thoracic region, the level of sensory disturbance may already indicate the affected level in the spinal column.

Furthermore, tumor-related fractures of the vertebral bodies may occur due to the destructive growth of the metastases. A possible consequence is compression of the spinal cord, which can lead to rapidly ascending paraplegia within a few hours. The destruction of the bone also leads to increased calcium levels in the blood, so-called hypocalcemia. In addition to symptoms such as rapid fatigue, muscle weakness, and concentration disorders, this can also result in numerous internal problems (such as constipation, pancreatitis, renal insufficiency, cardiac arrhythmias, and even coma).

Patients who belong to the risk group for vertebral metastases due to a previous malignant disease should therefore consult their treating physician promptly when symptoms appear. This is because the more severe the neurological disorders are, the lower the probability of complete recovery through treatment.

The Brice-McKissock classification is used to determine and grade the severity of clinical symptoms.

| Degree of disturbance | Description | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | low | Patient can walk. |

| 2 | moderate | Patient can move legs, but not against gravity. |

| 3 | serious | Low residual motor and sensory functions |

| 4 | complete | Motor and sensory functions are no longer present, the tension of the sphincter is extinguished. |

How are vertebral metastases diagnosed?

If corresponding symptoms are present, a neurological examination is first performed to confirm the suspicion of spinal metastases. If the suspicion is substantiated, imaging must be performed:

Magnetic resonance imaging

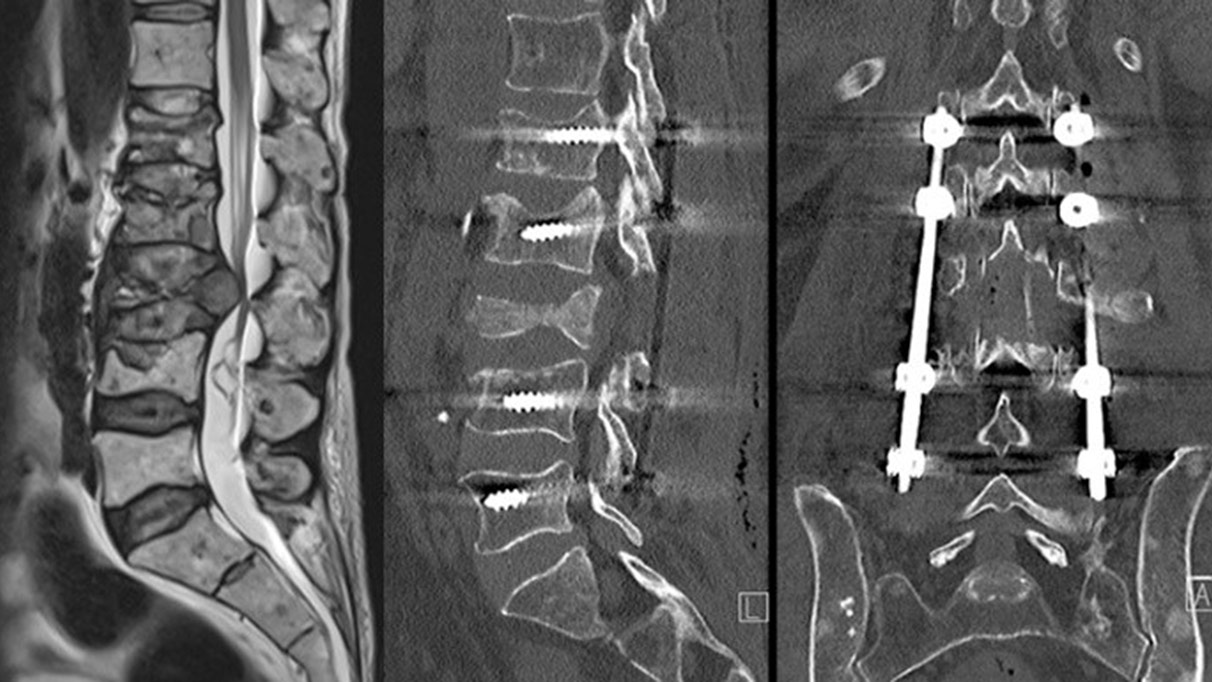

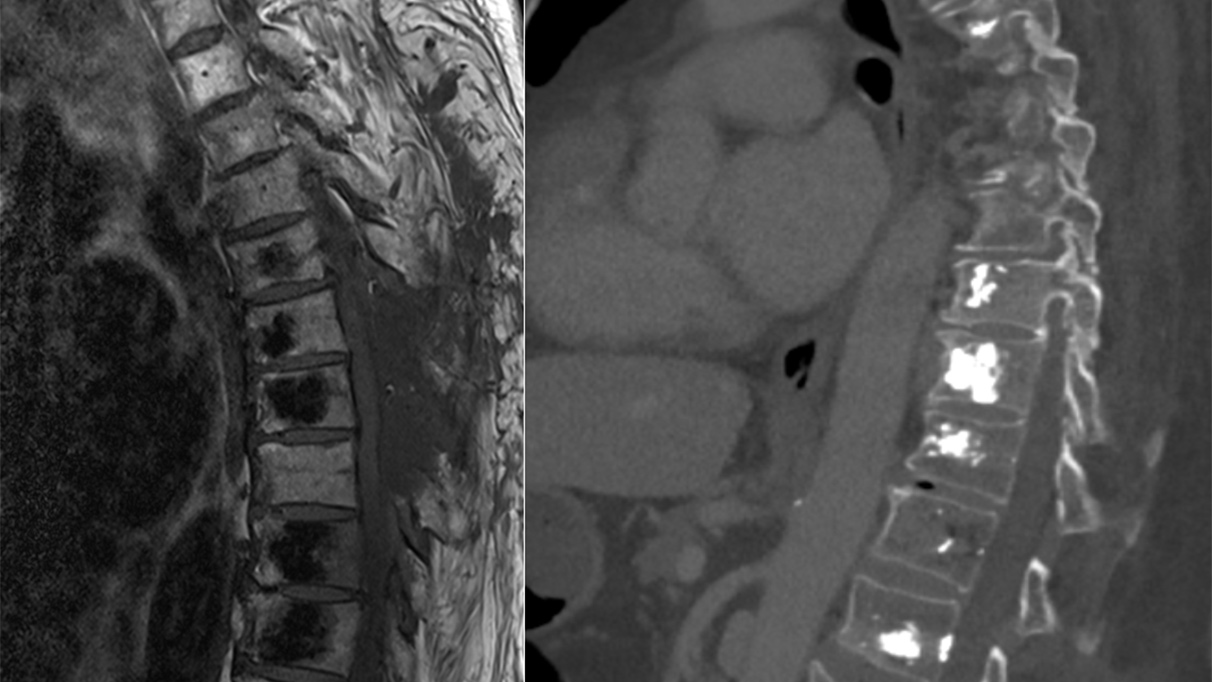

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) uses a magnetic field to visualize soft tissue conditions in detail. It offers the possibility of differentiating spinal metastases from other diseases of the spine. The examination is performed with contrast medium.

Computed tomography

Computed tomography (CT) is an imaging technique that can be performed quickly in many cases. It shows bone structures in detail. It is not as sensitive as an MRI for imaging spinal metastases. The examination is performed with X-rays and, in addition, usually with a contrast medium for better visualization of the tumor..

Positron emission tomography

Positron emission tomography (PET) is a whole-body screening method used in nuclear medicine to detect metastases in patients with known carcinoma. Sensitivity is high, but image morphological detail is low. At the end of 2020, the world's fastest PET-CT scanner was put into operation at the University Department of Nuclear Medicine at Inselspital. Using the latest technology, this scanner enables excellent examination quality with shorter examination times and reduced radiation exposure for our patients.

X-ray

An X-ray is a quick and easy examination to perform. However, it is not specific, so that only indirect signs of metastasis such as pathological fractures or changes in the bone structure can be revealed.

Digital subtraction angiography

Digital subtraction angiography (DSA) is necessary only in exceptional cases and is used primarily in the diagnosis of vascular pathologies and for their diagnostic differentiation from tumors (e.g. arteriovenous malformations (AVM) with myelopathy signal in MRI imaging).

In addition to the decisive imaging examinations, increased activity of alkaline phosphatase, hypocalcemia, and an increased value for the prostate-specific antigen (PSA) are often found in prostate carcinoma. For an accurate diagnosis, tumor markers must be determined during the tumor search. CSF diagnostics rarely yield decisive cytological findings.

What is the therapy for vertebral metastases?

Metastases in the spine represent a complex situation in the context of an underlying malignant systemic disease. Therefore, therapy planning always occurs in an interdisciplinary manner with the treating oncologists, radio-oncologists, and neurosurgeons.

Classification of patients

The urgency of the clarification and treatment depends on the respective neurological status of the patient. Here, a distinction is made between three groups:

Group 1: Emergency

New symptoms of a new or progressive neurological disorder due to spinal cord compression have a high risk of rapid deterioration. Therefore, rapid diagnosis and urgend treatment within hours are necessary.

Group 2: Urgent

Mild or stable symptoms of neurologic dysfunction due to spinal cord compression and signs of nerve root irritation or damage (radiculopathy) should be assessed within 24 hours and then treated promptly if necessary.

Group 3: Elective

Back pain without neurological disorders can be clarified on an outpatient basis within days, and treatment can be carried out as scheduled.

Therapy choice

The choice of therapy depends on the type of underlying carcinoma, the localization, the stability of the spine, the duration and severity of symptoms, and the patient's general condition. Various classification systems (Tomita Score, Tokuhashi Score, or Spinal Instability Neoplastic Score) help in deciding whether surgery is necessary and, if so, what type of surgery. However, these classifications are not universally applicable and therefore do not always help in decision-making. Rather, they guide what is essentially an interdisciplinary decision-making process.

The primary goal of therapy is to reduce (debulk) or completely resect the tumor to relieve pressure on the spinal cord and affected nerve roots and provide pain relief.

The choice is a combination of the following therapeutic options:

Drug treatment

Cortisone helps to reduce the acute swelling and pressure on the nerve structures. This can temporarily reduce symptoms and significantly reduce pain.

Bisphosphonates originate from the treatment of osteoporosis. They can prevent further bone loss and also bring about pain relief.

Hormone preparations are also used for some tumors.

Irradiation of the tumor

Radiation of the tumor in our Department of Radio-Oncology can effectively reduce tumor cells. Technically, different types of irradiation are used. It can be performed as a stand-alone treatment or can be performed following surgery.

Surgery

Surgery becomes necessary when there is rapid neurologic deterioration that has not been present for long. The most commonly used technique to decompress the spinal cord is laminectomy, in which part of the bony vertebral body is removed. However, this does not always reach the tumor well and creates further instability of the spine.

If there is instability or relevant deformity due to damage to the bony structures, stabilization and reconstruction of the spinal structures must be performed. Classification systems such as the SINS score are used to assess whether surgical stabilization is necessary. Factors such as localization of the metastasis, the extent of damage, and position of the vertebral bodies in relation to each other are considered *.

Kyphoplasty or vertebroplasty

A kyphoplasty or vertebroplasty is a treatment used for pathological fractures of the vertebral bodies. In both methods, cement is inserted into the vertebral body through a small incision. In kyphoplasty, a balloon is inflated in the vertebral body for this purpose, forming a cavity into which the bone cement is then filled in a controlled manner. This method primarily treats pain and leads to a functional improvement in 84% of those affected.

What is the prognosis for vertebral metastases?

The overall prognosis in cancer patients with bone metastases is basically dependent on the prognosis of the primary tumor. Priorities for us are pain control, preservation of spinal stability, and prevention or at least improvement of a paraplegic syndrome. Overall, numerous factors can improve or worsen prognosis *.

Favorable factors are:

- no metastases in other organs

- a single bone metastasis

- carcinomas of the breast and kidney, lymphomas or myelomas as primary tumors

Unfavorable factors are:

- multiple metastases

- pathological fractures

- lung carcinoma as primary tumor

- failure of neurological functions

The status of neurological functions prior to surgery or other therapies also significantly determines the outcome. In particular, walking ability and sphincter function are essential; thus, complete loss of sphincter function is an unfavorable prognostic factor and is usually irreversible *.

The location of metastasis in the skeleton does not explicitly affect prognosis, but significantly determines the options for surgical treatment.

-

Abeloff MD, Armitage JO, Niederhuber JE, Kastan MB, McKenna WG. Abeloff’s Clinical Oncology E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2008:2592.

-

Algra PR, Heimans JJ, Valk J, Nauta JJ, Lachniet M, Van Kooten B. Do metastases in vertebrae begin in the body or the pedicles? Imaging study in 45 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1992;158:1275-1279.

-

Greenberg MS. Handbook of Neurosurgery. Thieme; 2016:1664.

-

Fisher CG, DiPaola CP, Ryken TC et al. A novel classification system for spinal instability in neoplastic disease: an evidence-based approach and expert consensus from the Spine Oncology Study Group. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2010;35:E1221-9.

-

Bauer HC, Wedin R. Survival after surgery for spinal and extremity metastases. Prognostication in 241 patients. Acta Orthop Scand. 1995;66:143-146.