Spinal stenosis of the lumbar spine is a common cause of walking difficulties in the elderly and is easily overlooked by doctors. Narrowing of the vertebral canal leads to a constriction of the nerves running there. Typical symptoms include pain, weakness or sensory disturbances in one or both legs, which occur after just a few minutes of walking and can lead to severe limitations for those affected. Studies show that surgery helps better than conservative treatment. The surgery of choice is microsurgical removal of the excess tissue to release the constricted nerves. This procedure has an immediate effect, a low complication rate, and results in significant long-term improvement in 8 out of 10 patients.

How does a narrowing of the spinal canal occur?

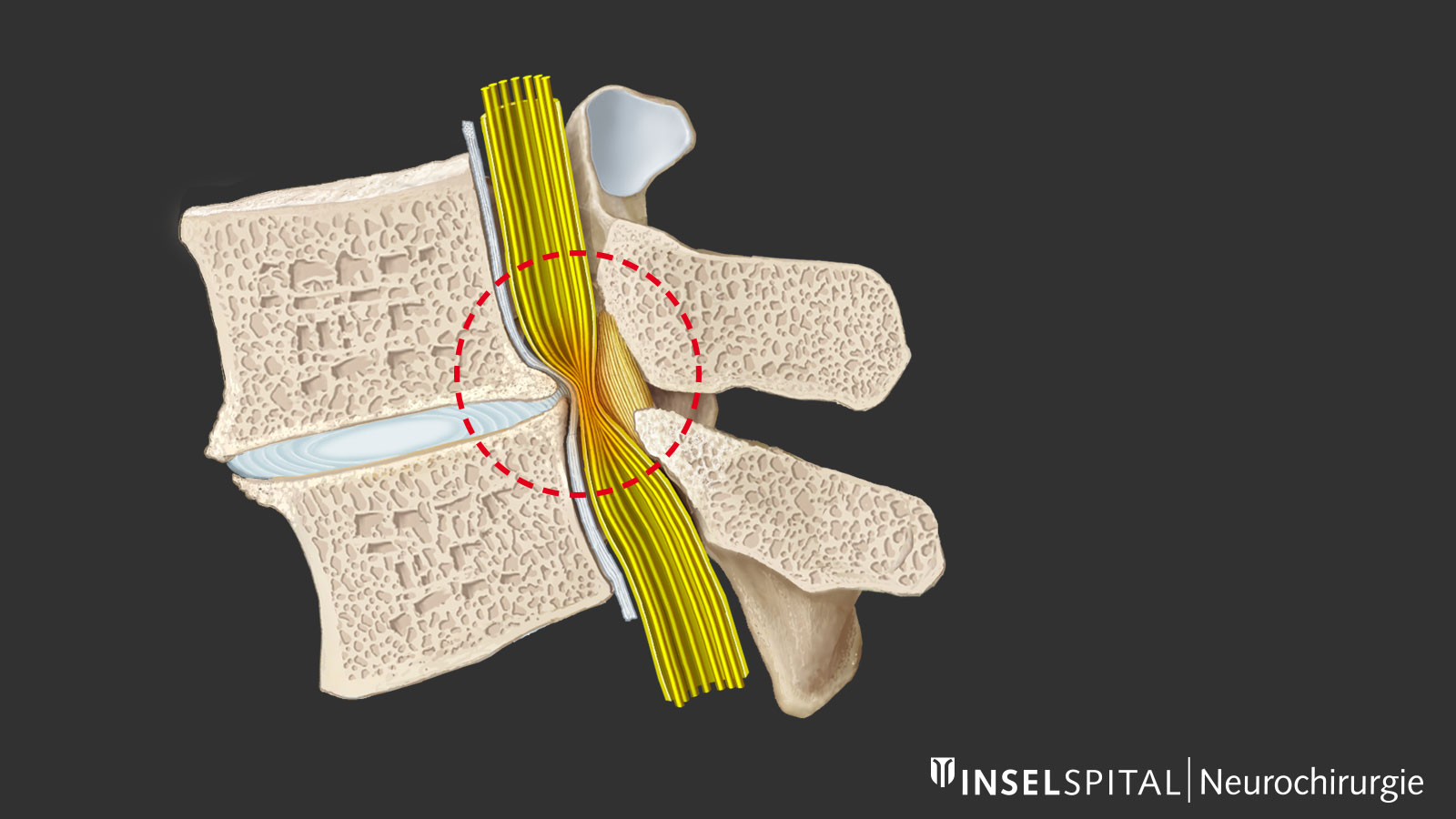

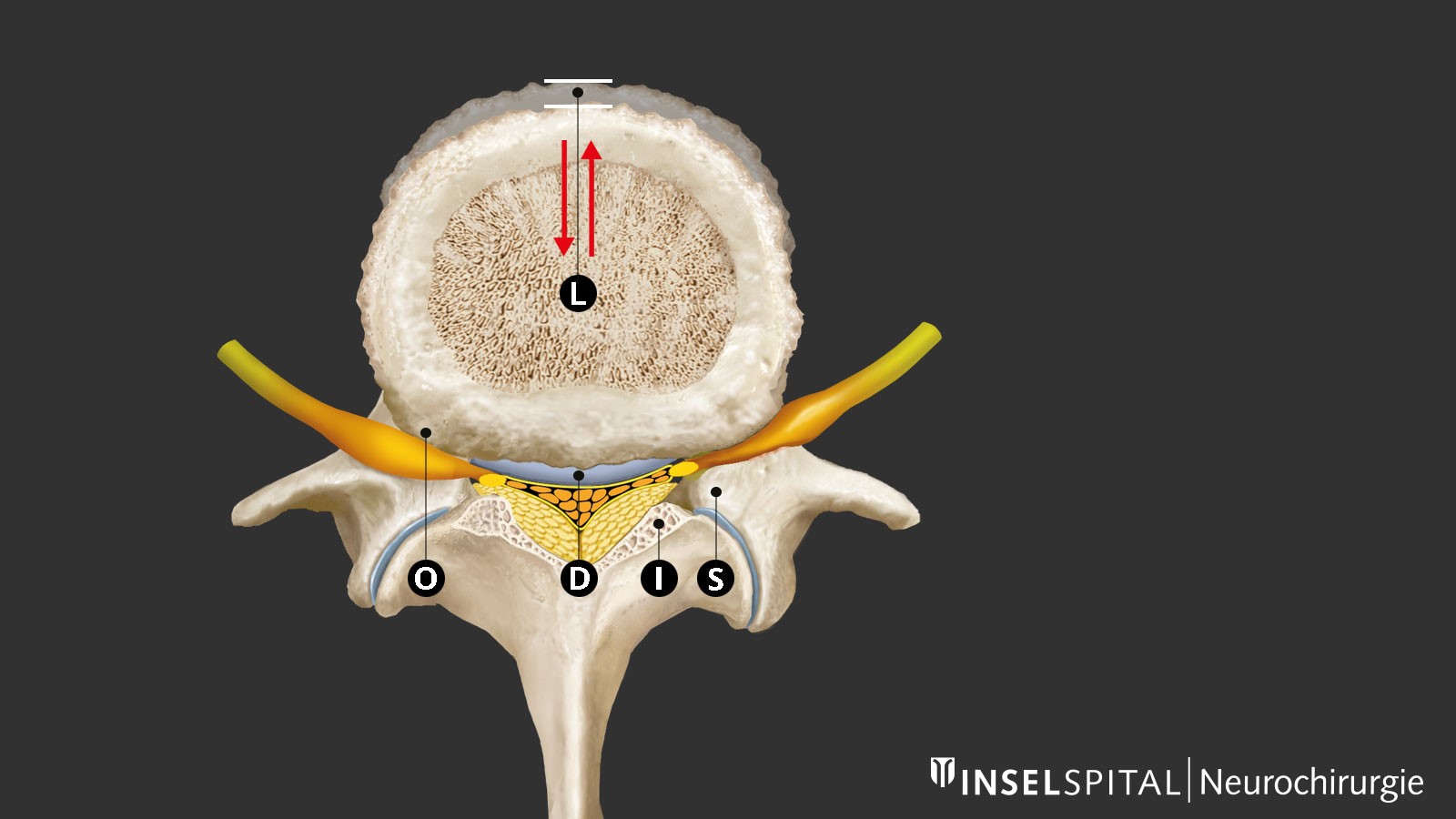

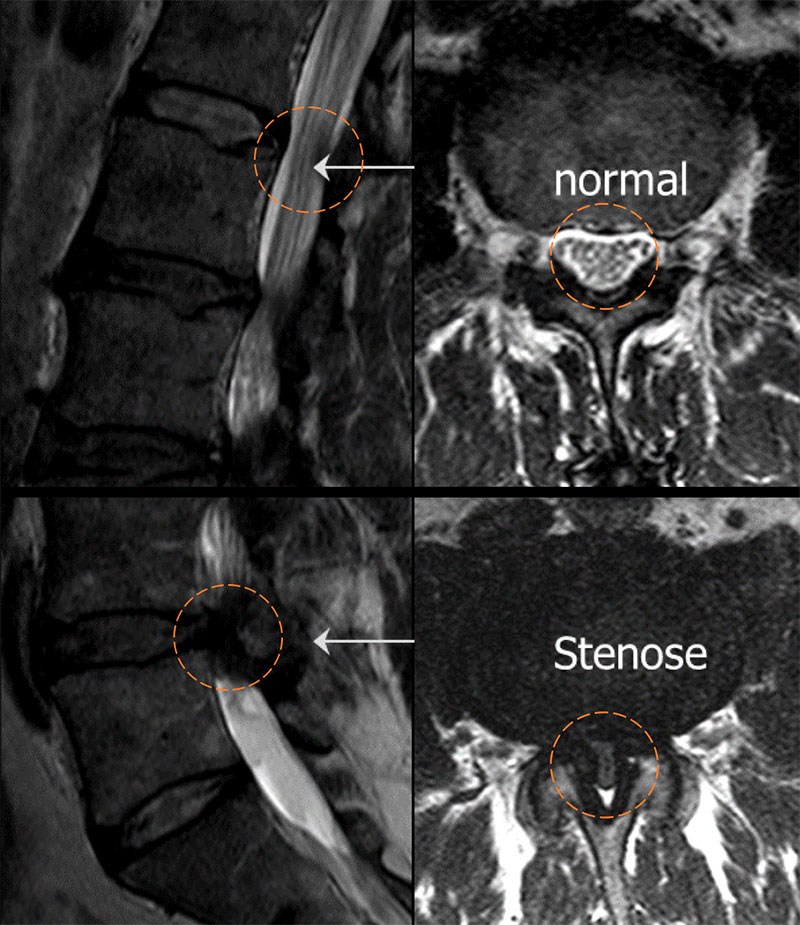

As the spine wears and ages, degenerative changes occur, which are most pronounced in the lower lumbar spine. A key role is played by dehydration of the intervertebral disc with loss of height and micromovements between two vertebra. The body reacts by trying to restabilize the spine through thickening of the ligamentum flavum and bone build-up or hypertrophy, especially at the facet joint. This causes central and lateral narrowing of the spinal canal and the intervertebral foramina with compression of the nerves centrally, recessively (recess stenosis) and less often foraminally when exiting the foramen. This stenosis of the spinal canal can be exacerbated by bulging of the intervertebral disc or, in rare cases, by vertebral slippage.

How common is spinal stenosis?

There are no reliable figures on the frequency of spinal stenosis. Except where constriction of the spinal canal is congenital, the disease typically occurs in the elderly. Women are more often affected than men (ratio 3:1). A radiologically narrow spinal canal occurs in 20–40% of older people. About 1–5% of all older patients with back pain have spinal stenosis that requires treatment. Stenosis can also arise within a relatively short time. Therefore, it may be advisable to have a repeat MRI after 2–3 years.

After operations on herniated discs, microsurgical treatment for spinal stenosis is the second most common back operation (13 operations per 100,000 inhabitants per year) and the most common operation for patients over 50 years of age.

Factors like the increasing life expectancy, the higher proportion of older people in the general population and the desire to continue an active lifestyle into old age are reasons why the clinical picture of spinal stenosis will gain in importance in the coming years.

What are the symptoms of spinal stenosis?

Typical complaints and key symptoms are:

- Difficulties with walking, and weakness or pain in the buttocks and/or legs, either one-sided or on both sides

- Back pain (lumbago) with various degrees of severity

- Improvement of the symptoms when in a bent posture or sitting down

Neurogenic claudication

Classic spinal stenosis manifests as pain in one or both legs, which occurs after walking a certain distance or after some time standing. Physicians call this neurogenic claudication. The leg pain can be accompanied by back pain. Typically, the pain is relieved by sitting, lying or cycling, but not by just standing still. This differentiates neurogenic claudication from intermittent claudication. It is also more comfortable to bend forward, for example when leaning on a shopping trolley. Some patients feel pain in their leg in any position whenever they hold their back straight, because stretching the spine reduces the internal diameter of the spinal canal, while flexion increases it. Cycling is therefore usually possible without any problems. 30% of patients do not experience typical symptoms of neurogenic claudication. Instead, sciatica-type complaints or paresthesia (tingling in the legs, leg cramps, weakness in the leg and pain at rest) occur.

Back pain

Back pain is one of the symptoms, but it can vary in intensity and is also load-dependent. In rare cases with associated vertebral slippage, pain due to instability of the spine may be predominant. Often back pain is a secondary problem caused by the constant bending over.

Neurological deficits

Disorders of sensation, motor skills and reflexes – if they occur at all – are quite mild. They mostly affect the skin and muscles for the L5 nerve root (weakness of the foot dorsiflexors, hypoesthesia of the big toe) or L4 (weakness of the quadriceps, hypoesthesia of the inside of the lower leg), and less often other nerve roots. However, the results of the neurological examination are often unremarkable. Acute paralysis is possible, but rare. So-called cauda equina syndrome, with dysfunction of the bladder or rectum due to compression of the dural sac, is rare.

How is spinal stenosis diagnosed?

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the lumbar spine is the first choice of diagnostic approach. The MRI image will show the thickening of the ligamentum flavum and the prominent intervertebral joints, which cause significant narrowing of the spinal canal. Also typical is the slight, but broad protrusion of the intervertebral disc which can often be seen sagittally. In most cases, the lumbar vertebrae L4/L5 or L3/L4 are affected. In patients with a congenitally narrow canal, multiple constrictions are found in middle age. A functional image of the lumbar spine during flexion and extension is necessary in patients whose dominant symptom is back pain in order to diagnose or rule out spinal slippage – so-called spondylolisthesis. Vascular (intermittent) claudication should be excluded on the basis of the typical clinical signs or with the help of a Doppler examination. Typical signs are the lack of a pulse in the foot, trophic skin changes, cold skin, discomfort even when in a bent position, for example when cycling, and muscle pain rather than nerve pain.

Getting a second opinion

The decision on whether to have an operation on your spine is not always easy. There are often several possible surgical methods to choose from, each with different advantages and risks that need to be weighed up. A second opinion helps you to make the right decision for you and confirms that your treatment reflects the state-of-the-art in medicine. Make an appointment with us at the neurosurgical polyclinic or arrange a consultation with the chief physician.

When is surgery needed for spinal stenosis?

Around 20–40% of people over the age of 60 years show signs of spinal stenosis on X-rays but report no complaints. In these cases, treatment is not necessary.

However, for people with obvious symptoms, surgery should be considered. In particular, for older patients with clear symptoms, the operation should not be postponed for too long; otherwise they will suffer loss of stamina due to increasing immobility and will become weaker. The operation is a routine procedure with a low complication rate – even for 70- to 90-year-old patients. Therefore, surgery is the treatment of choice even in elderly people.

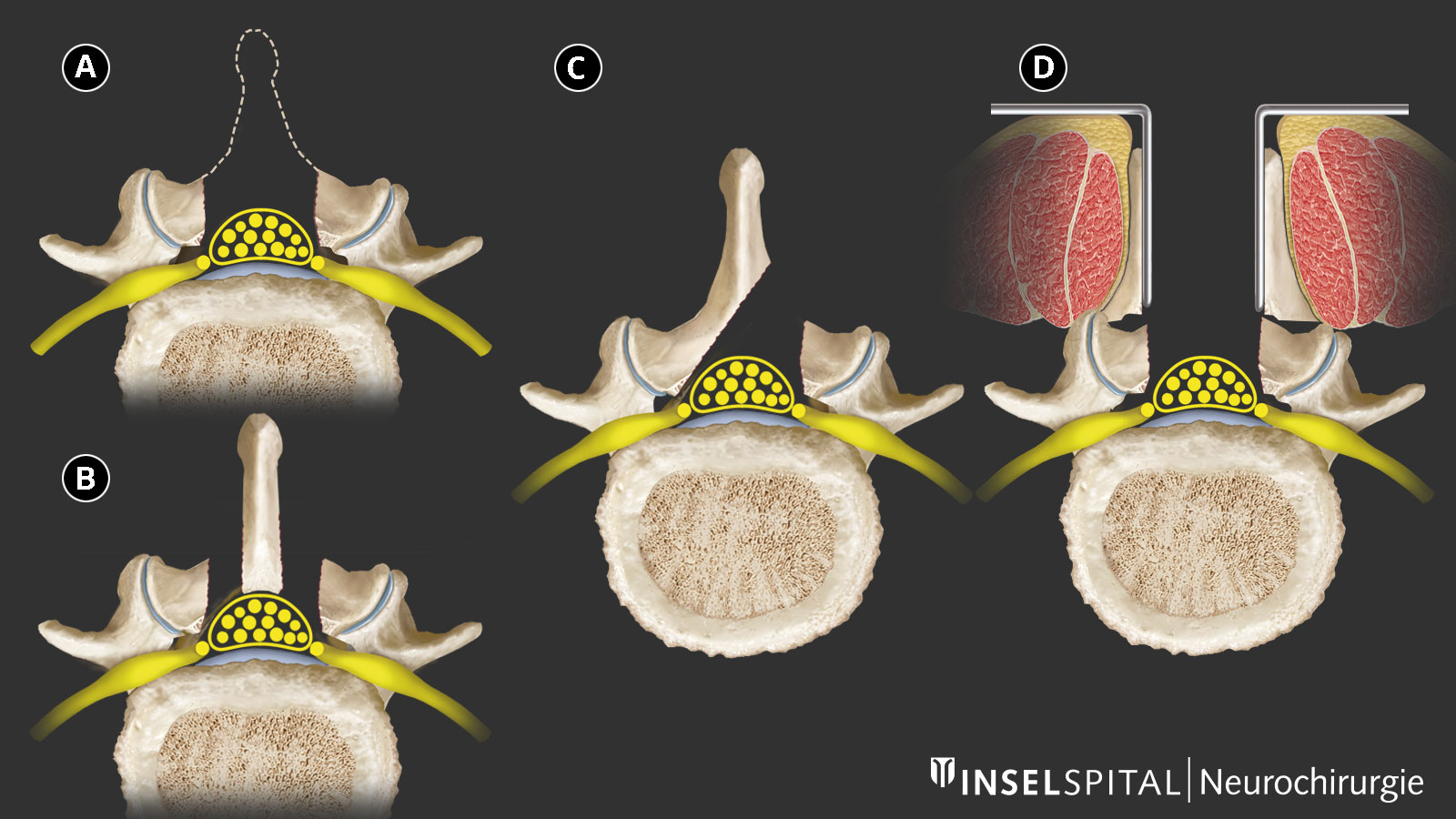

Minimally invasive surgery for spinal stenosis

During surgery for spinal stenosis, the constriction is removed under a surgical microscope, the compressed nerves are freed and the internal diameter of the spinal canal is re-enlarged. The surgical technique has increasingly developed into a minimally invasive approach. At the Inselspital, surgeons use minimally invasive keyhole access – taking care to spare the muscles and joints – ensuring maintenance of movement (no routine fusion of the vertebrae) and preservation of the spinous processes and posterior ligaments of the spine. This procedure results in only a small entry wound and maintains the stability of the spine.

What is the success rate of this surgery?

Most patients, about 7–8 out of 10 (70–80%) feel the beneficial effects of the surgery straight away. The pain is noticeably reduced, and the distance the patient can walk normalizes or is significantly extended. This improvement usually lasts for years. The success of the operation is most evident in the reduction of leg pain, but back pain also often disappears.

It is important to remember that the spine remains the same and occasional residual complaints are unavoidable. In addition, new degenerative changes can arise over time. It is assumed that about 10% of the patients will have to be operated on again after about 5 years, mostly due to further wear on the neighboring vertebrae or on the operated segment itself.

In 2 out of 10 patients, significant residual symptoms remain or recur. The causes are nerve-related pain, residual pain emanating from the spine or the formation of scar tissue.

Microsurgical decompression is very safe even in elderly patients. Severe and persistent complications affect only 1 in 100 patients (1%). This includes injuries to the nerves, heart attacks, pulmonary embolism and other rare life-threatening incidents. This extremely low number of complications has been confirmed in several international studies.

Mild and temporary complications that do not cause any permanent damage include:

- Leakage of cerebrospinal fluid from the dural sac in 1 in 20 patients (5%). This is due to adhesion of the dural sac to the stenosis. This usually very small leak is sealed immediately during the operation.

- Bleeding in 1 in 50 patients (2%). In some cases, the bleeding needs to be stopped by a simple second operation.

- Infection in 1 in 50 patients (2%). If infection develops, antibiotics are given and the wound is cleaned.

The mortality rate within 90 days after the operation – a marker of the severity of the procedure – is only 2 in 1,000 patients (0.2%) despite the older patient age of 60–90 years *.

What happens after the surgery and how long is the hospital stay?

The surgery is carried out under general anesthetic and takes about 30–60 minutes per segment. Afterwards, the patient remains under observation in the recovery room for about 4 hours before being moved back to his or her room. With the assistance of a nurse, the patient is encouraged to stand up immediately. The day after surgery, instructions are given by our physiotherapists, who begin full mobilization immediately if possible. Sometimes patients have local wound pain after the procedure. However, in 8 out of 10 patients, the leg pain disappears immediately after surgery. These patients can walk unaided, climb stairs and quickly find their way back to normal mobility. Painkillers such as acetaminophen, novalgin or ibuprofen are prescribed as needed. Usually, patients go home after 2 to 5 days, depending on their individual needs, home support and residual pain. Inpatient rehabilitation in another clinic after discharge from hospital is usually not necessary.

What happens after discharge from hospital?

We recommend a gradual return to normal mobility in the first few days after surgery. However, the speed of the return to normal everyday activities and physical exertion depends on age, general state of health, comorbidities and residual symptoms. Even though patients can take longer walks after discharge from the hospital, we do not recommend strenuous exercise, heavy lifting, or activities involving rotation or flexion of the spine in the first 4–8 weeks, so that the wound has time to heal properly, even deep down. Gentle swimming or light jogging are possible from 3 weeks after the operation. Although our physiotherapists inform patients about optimal posture, exercise and back training, and provide explanatory material during the hospital stay, outpatient physiotherapy can often be helpful. Inpatient rehabilitation is only necessary in exceptional cases. We also organize household help for patients who live alone and are in need of support.

Do vertebrae have to be screwed and fused?

Normally, screws for the vertebrae or spinal fusion are not necessary. The most common type of stenosis consists of a strict narrowing without any visible instability of the spine. In many cases the area of the operation is bigger than necessary because it is argued that the spine can become unstable at the site of the stenosis. However, this only happens in a small minority of patients. In our patients with spinal stenosis, only 3% required fusion due to instability in the 5 years following minimally invasive decompression *. If the vertebral displacement does not exceed 3 mm at the start of movement, primary fusion can be dispensed with *.

Another argument against fusion surgery is that the neighboring vertebrae are subjected to greater stress and wear out faster. This is the case in 3–4% of patients with spinal fusion surgery each year. As a result, about half of these patients have to be operated on again. This rate is thus higher than the frequency of instability after minimally invasive decompression surgery.

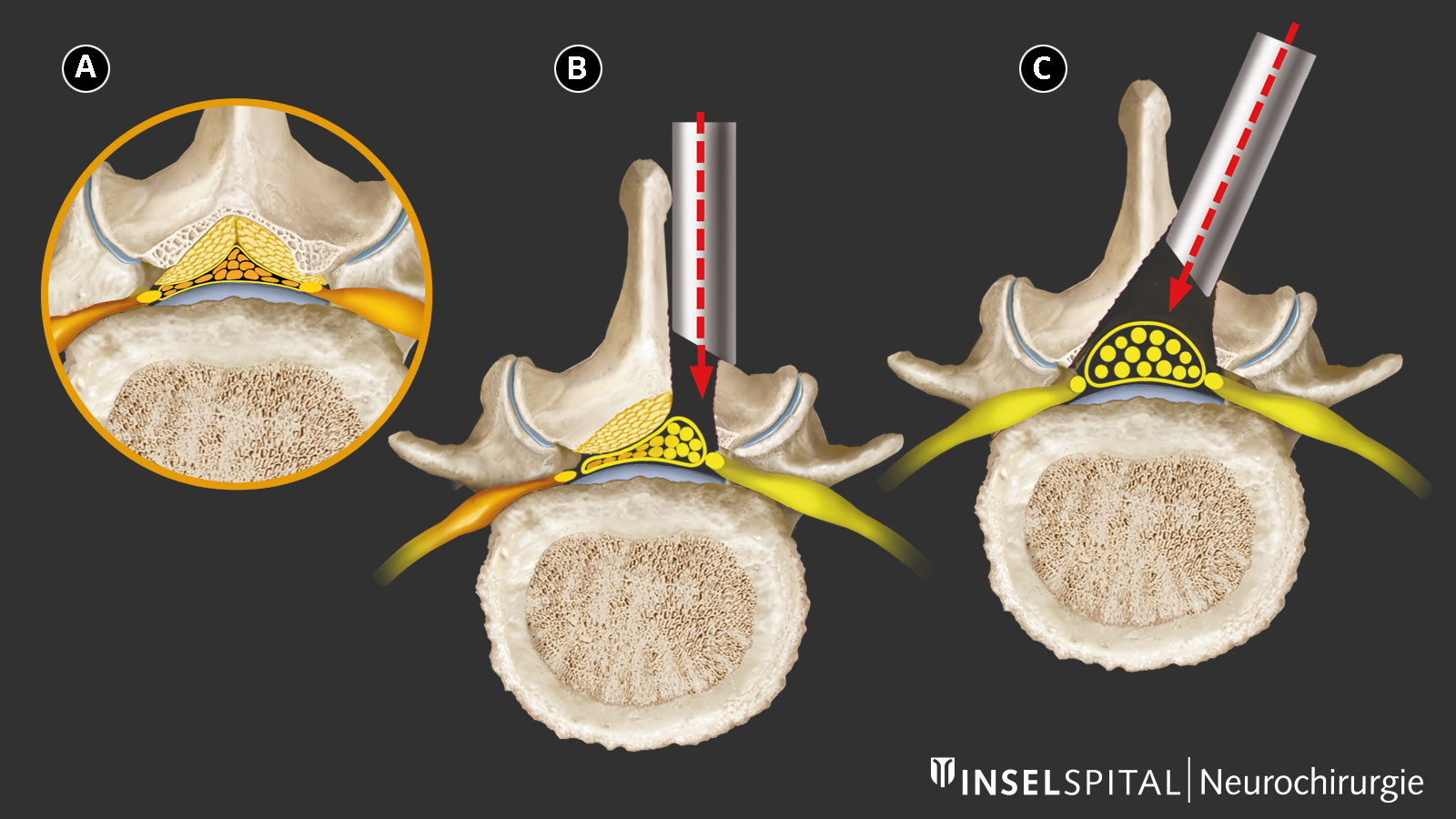

Modern minimally invasive microsurgical techniques

The so-called laminectomy is obsolete. This is a procedure in which the entire rear portion of the spinal canal (i.e. the spinous process and vertebral arch) in the narrowed segment is removed. This procedure destabilizes the spine and is not minimally invasive.

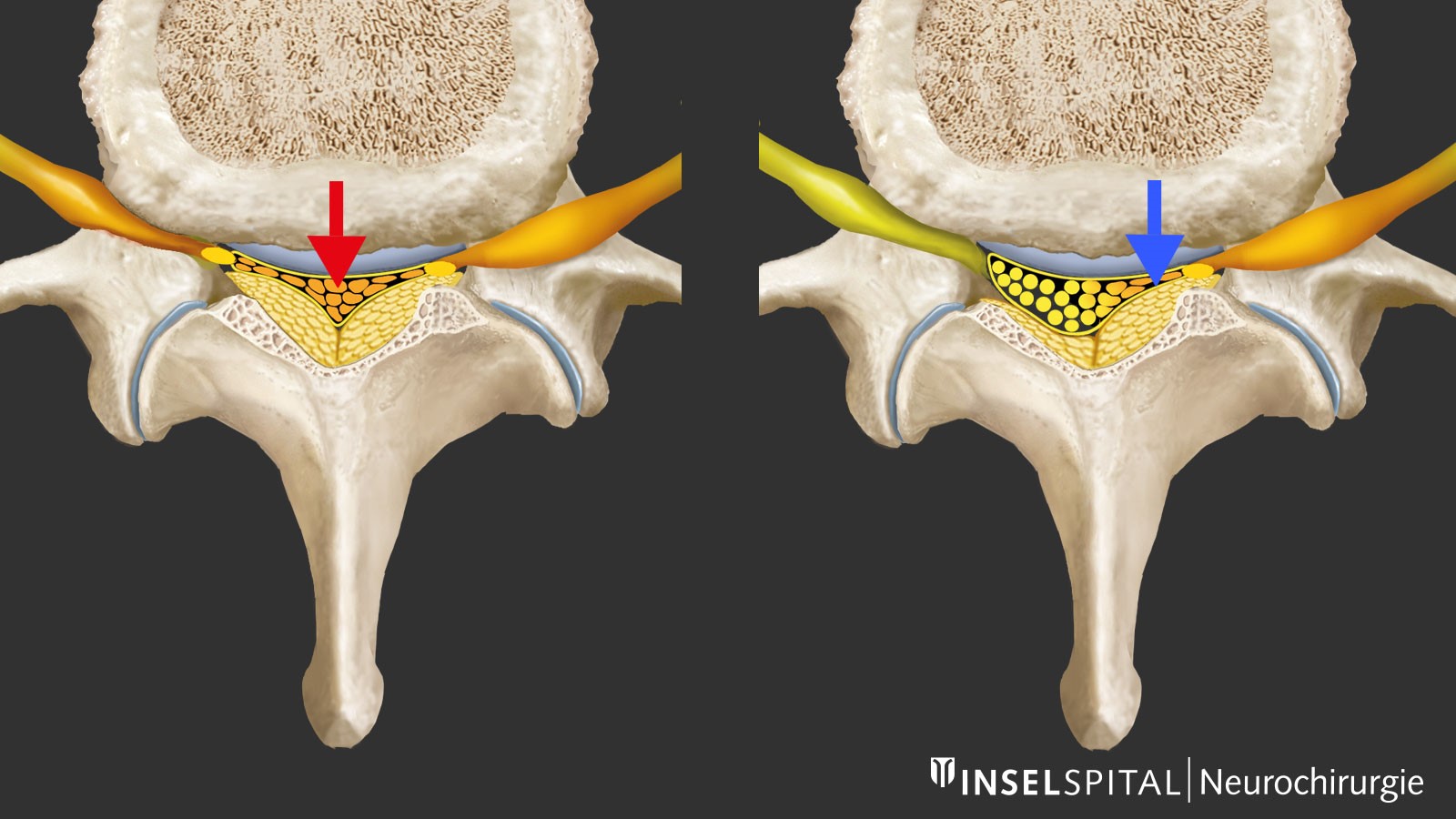

Nowadays, only the excess bone and ligamentous growth that presses on the nerves is removed, either by splitting the spinous process or with unilateral or bilateral access. The spinous process, stabilizing ligaments and vertebral arches are spared. The surgeon decides on the method of access after looking at the images from magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and the general health of the patient.

Access via a tube system, so-called tubular access, also protects the muscle attachments and further reduces the area affected by the procedure.

Non-surgical treatment for spinal stenosis

Conservative management of spinal stenosis is only effective to a limited extent because the symptoms are due to compression of the nerve roots. Back exercises, physiotherapy, an activity program, painkillers (paracetamol, anti-inflammatory medicines, flupirtine, gabapentin), trigger point- or facet infiltration with local anesthetics and corticosteroids (triamcinolone) only lead to short-term improvement of the patient's condition and usually cease to work quite quickly. Generally, surgical decompression of the narrowed nerves is essential for long-term improvement of the symptoms. This has been scientifically proven in several studies.

Study comparing surgery with conservative treatment

Surgery yields better results than conservative treatment for patients with spinal stenosis. The results of the biggest prospective randomized controlled study comparing surgery with conservative management shows this clearly *. This investigation provides the strongest medical evidence for the benefits of spinal stenosis surgery. The benefits of the operation also continue for many years *.

Are there alternative surgical procedures?

Interspinous spacer

Another minimally invasive procedure consists of the implantation of an interspinous spacer. The spacer is implanted between two interspinous processes. This implant forces the affected segment into an (unnatural) forward bend, a so-called kyphosis. In this way, the internal diameter of the spinal canal is increased. However, this process is characterized by a high failure rate over the long term and should only be performed as an exception in patients with a high general surgical risk. In the medium term, it also leads to increased wear and tear of the surface of the vertebral segments.

Instrumentation and fusion

These technical terms refer to the screwing and stiffening of a section of the spine. This includes surgical interventions performed from the front, the side and most often from behind, the latter with the implantation of at least 4 screws in adjacent vertebrae. These screws are connected with titanium rods to bring the vertebrae back into the correct position and stabilize them. For permanent fusion the intervertebral disc would also be removed and replaced with an implant (spacer). This additional support prevents the screws from gradually loosening and breaking. So-called dynamic stabilizations have also been used, but they ossify over time and have therefore not become established in practice.

The insertion of screws and the removal of the intervertebral disc with fusion is only necessary if, according to defined criteria, overt mobile instability, so-called spondylolisthesis, is visible on the MRI scan and the corresponding symptoms are present. However, this condition does not affect more than 5% of patients. If in doubt, patients should seek a second medical opinion.

-

Schär RT, Kiebach S, Raabe A, Ulrich CT. Reoperation Rate After Microsurgical Uni- or Bilateral Laminotomy for Lumbar Spinal Stenosis With and Without Low-grade Spondylolisthesis. SPINE. 2019;44(4):E245-E251.

-

Peul W, Moojen W. Fusion for Lumbar Spinal Stenosis – Safeguard or Superfluous Surgical Implant?. New England Journal of Medicine. 2016;374(15):1478-1479.

-

Weinstein J, Tosteson T, Lurie J, Tosteson A, Blood E, Hanscom B et al. Surgical versus Nonsurgical Therapy for Lumbar Spinal Stenosis. New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;358(8):794-810.

-

Weinstein J, Tosteson T, Lurie J, Tosteson A, Blood E, Herkowitz H et al. Surgical Versus Nonoperative Treatment for Lumbar Spinal Stenosis Four-Year Results of the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial. Spine. 2010;35(14):1329-1338.